Gentrification has long been a subject of intense debate among urban scholars and city planners. While some view it as a necessary evolution of urban landscapes, bringing investment, economic growth, and revitalization, others highlight its darker side—the displacement of working-class communities and the commodification of cultural heritage.

At its core, gentrification is both a cultural and a political process, driven by economic forces, urban policies, and changing aesthetic preferences.

The Roots of Gentrification: From Theory to Reality

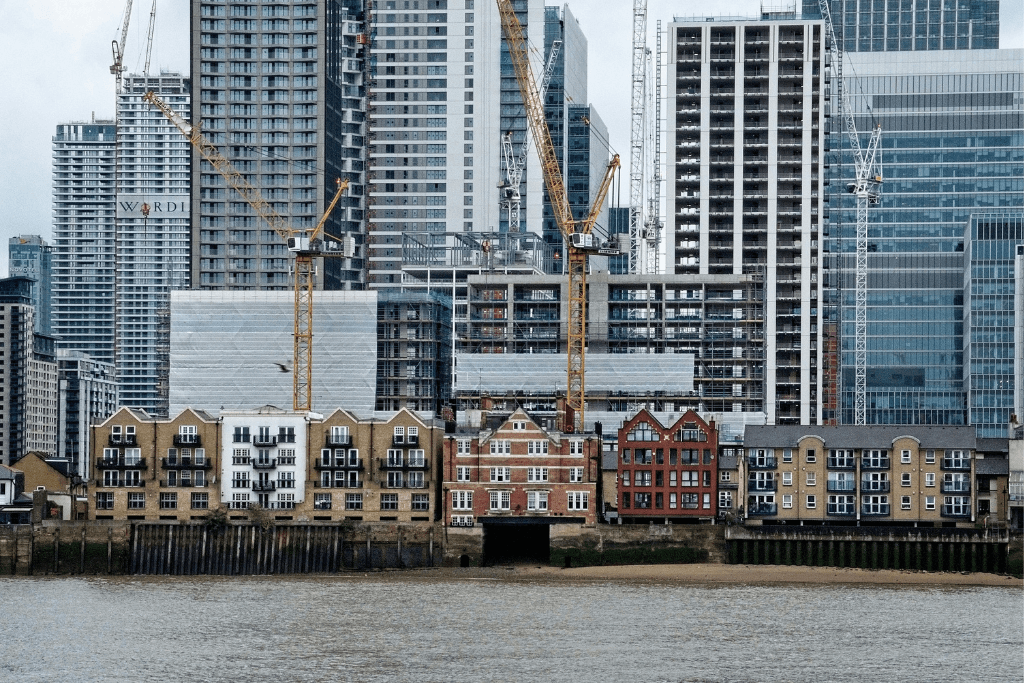

The term gentrification was first coined in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass to describe the transformation of working-class neighborhoods in London as wealthier residents moved in, displacing original inhabitants. Over time, scholars have sought to explain this phenomenon through various lenses, leading to two dominant schools of thought: supply-side and demand-side explanations.

On the supply side, theorists such as Neil Smith argue that gentrification is primarily driven by economic cycles and property market dynamics. His rent-gap theory suggests that gentrification occurs when the difference between a property’s actual value and its potential value reaches a tipping point, attracting investors and developers.

Governments and financial institutions play a crucial role by either facilitating or restricting investment in certain areas, further accelerating or impeding the process.

Conversely, demand-side theorists like David Ley emphasize cultural and social factors, arguing that the preferences of the so-called “new middle class”—comprising young professionals, creatives, and entrepreneurs—drive the transformation of urban spaces.

These individuals often seek vibrant, historic, and aesthetically rich neighborhoods, favoring city centers over suburban life.

Beyond Economics: The Cultural Dimensions of Gentrification

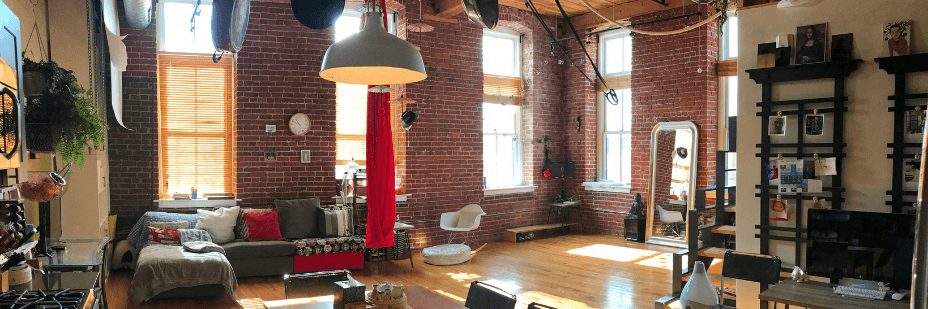

While economic structures set the stage for gentrification, cultural shifts determine its trajectory. In her groundbreaking work “Loft Living”, urban sociologist Sharon Zukin explored how artistic and bohemian communities played a pivotal role in rebranding industrial neighborhoods. Her analysis of Manhattan’s SoHo district revealed a recurring pattern: once artists and creatives transformed abandoned industrial spaces into desirable living and working environments, real estate developers followed, driving property values sky-high.

Zukin argued that gentrification is not merely an economic process but also a cultural one, where taste, aesthetics, and social status become commodities. The process begins with cultural pioneers—often artists, musicians, and writers—who introduce new ways of living that appeal to a broader audience. As demand for these spaces grows, businesses catering to higher-income residents emerge, ultimately leading to the displacement of lower-income communities.

The Political Engine Behind Urban Transformation

Government policies and urban planning decisions significantly influence the pace and scale of gentrification. Many cities actively encourage redevelopment through tax incentives, zoning changes, and infrastructure improvements, often under the guise of urban renewal or sustainability initiatives.

While these policies may stimulate investment, they can also lead to unintended consequences, such as the exclusion of long-term residents from their own neighborhoods.

For example, in cities like New York, London, and Berlin, rising rents and property prices have forced working-class communities to relocate, fueling protests and policy debates about affordable housing, tenant protections, and social equity.

The tension between economic growth and social justice underscores the political dimension of gentrification, highlighting the need for balanced approaches that ensure inclusivity while fostering development.

Winners and Losers: The Social Impact of Gentrification

One of the most contentious aspects of gentrification is its human impact. While proponents argue that it revitalizes neglected areas, improves infrastructure, and enhances public safety, critics emphasize the displacement of long-term residents and the erosion of local cultures.

A typical gentrification cycle follows a familiar pattern:

- Neglected neighborhoods with affordable housing and rich cultural histories attract artists and young professionals.

- Businesses and investors capitalize on the growing appeal, leading to rising rents and property prices.

- Long-term residents and small businesses struggle to keep up, eventually being pushed out by wealthier newcomers.

- The neighborhood undergoes a complete socio-economic transformation, often losing its original character.

Cities worldwide have responded in different ways, with some implementing rent control measures, community land trusts, and affordable housing initiatives to mitigate negative effects. However, achieving a balance between economic development and social preservation remains a persistent challenge.

The Future of Gentrification: Towards More Inclusive Urban Growth

As cities continue to evolve, so does the conversation around gentrification. Mixed-income housing policies, community-driven planning, and equitable investment strategies offer potential solutions for creating more inclusive urban environments.

Instead of viewing gentrification as an inevitable force, city planners and policymakers have the opportunity to shape it in ways that benefit both new and existing residents.

Urban sociologists like Loretta Lees and Sharon Zukin advocate for an integrated approach that considers both economic and cultural dimensions, ensuring that redevelopment efforts do not come at the expense of marginalized communities.

Meanwhile, grassroots movements are pushing for policies that prioritize housing as a fundamental right rather than a commodity.

A Complex, Multifaceted Phenomenon

Gentrification is neither wholly beneficial nor entirely harmful—it is a complex phenomenon shaped by economic, cultural, and political forces. While it can bring new life to neglected areas, it also poses significant challenges in terms of affordability, social equity, and cultural preservation.

As cities around the world grapple with these dynamics, one thing remains clear: a thoughtful, inclusive approach to urban development is essential.

By recognizing both the benefits and drawbacks of gentrification, policymakers, communities, and developers can work together to create vibrant, diverse, and sustainable urban spaces that serve all residents—not just the privileged few.